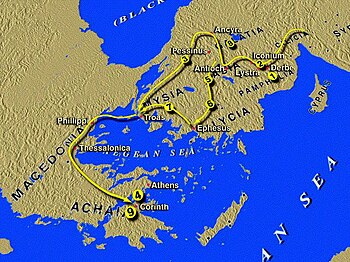

| English: Map of the Letters of Galatia (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

In

the first entry in the Bible Junkies Online Commentary on Galatians, I

discussed introductory matters concerning the founding of the churches to the

Galatians, the situation when Paul wrote to them, when the letter might have

been written and the type of letters which Paul wrote, based on the common

Greco-Roman letters of his day. In

the second post, I considered the basic content and breakdown of a Pauline

letter. I noted the major sections of the formal letter structure and, in the

context of each section, outlined the theological and ethical (as well as

other) concerns of Paul, including some Greek words which will be examined more

fully as we continue with the commentary. In

the third entry, I looked at the salutation, which is long for Paul’s

corpus (only Romans 1:1-7 is longer) and briefly commented on the lack of a

Thanksgiving, the only letter of Paul’s which does not have one. The

fourth entry discussed the opening of the body of the letter, a significant

part of the letter especially in light of the absence of a Thanksgiving. In

the fifth entry, I examined the beginning of the opening of the body of the

letter, in which Paul describes his background in Judaism and I placed this in the

context of Judaism in the Hellenistic period. In the

sixth post in the online commentary, I continued to look at Paul’s

biographical sketch of his life, this concerning his earliest life as a

Christian. In

the seventh post, I examined what Paul says about his subsequent visit to

Jerusalem to see the apostles and the Church in Jerusalem.

In the eighth entry, Paul confronts Cephas about his hypocrisy in

Antioch.

The

ninth blog post started to examine the theological argument in one of

Paul’s most important and complex theological letters. In

the tenth entry, Paul makes an emotional appeal to the Galatians based on

their past religious experiences and their relationship with Paul. In

the eleventh chapter in the series, Paul began to examine Abraham in light

of his faith. The

twelfth blog post continued Paul’s examination of Abraham, but also claims

that Christ “redeemed” his followers from the “curse” of the Law. In

the thirteenth study in the Galatians online commentary, we looked at Paul’s

claim that God’s promises were to Abraham and his “offspring,” with a twist on

the meaning of “offspring.” The

fourteenth entry examined Paul’s question, in light of his claims about the

law, as to why God gave the law. The

fifteenth chapter in this commentary examines the function of the law,

while the

sixteenth post studied how the members of the Church are heirs to the

promise. This, the seventeenth entry, observes what it means to be an heir in

Paul’s theological scenario.

4. Paul’s Letter to the Galatians

d) Body of the Letter (1:13-6:10):

iv) Theological Teaching (2:15-5:12): Why

then the law? (4:1-7) part 4.

1 My point is this:

heirs, as long as they are minors, are no better than slaves, though they are

the owners of all the property; 2 but they remain under guardians and trustees

until the date set by the father. 3 So with us; while we were minors, we were enslaved

to the elemental spirits of the world. 4 But when the fullness of

time had come, God sent his Son, born of a woman, born under the law, 5 in

order to redeem those who were under the law, so that we might receive adoption

as children. 6 And because you are children, God has sent the Spirit of his Son

into our hearts, crying, "Abba! Father!"

7 So you are no longer a slave but a child, and if a child then also an heir,

through God. (NRSV)

In

the previous entry, Paul focused on how disciples of Jesus became heirs to

the promise of Abraham. In this passage, Paul further continues his explanation

of the law as having a limited function by drawing on the reality of a child in

antiquity coming to maturity. This depiction continues to draw on the well-known

role and function of the paidagôgos,

the person, generally a slave, whose task was to guard a boy until he reached

maturity. Paul sees the law as the paidagôgos

whose role has reached an end since the follower of Jesus, through faith in

him, has become an adult, free from the constraint of the paidagôgos. In fact, Paul says, such a person is now an “heir” (klêronomos) to all of the promises given

to Abraham.

Paul says, “My point

is this: heirs, as long as they are minors, are no better than slaves, though

they are the owners of all the property” (Galatians 4:1). This connects to the paidagôgos because every boy under the

authority of the paidagôgos, the law

in Paul’s narrative, was a minor. Paul actually uses the word nêpioi here, which literally translates

as “infants.” It was often the case that free children, as noted before, remained

under the authority of slaves who were their paidagôgoi, but it is somewhat hyperbolic of Paul to say that such

freeborn children “are no better than slaves.” Free children, when the time

came, were simply much better off than slaves, but the point is a rhetorically powerful

one: What is an heir who cannot inherit? Now that the time of maturity has come,

the inheritance has also arrived.

Paul does complicate

matters, though, when he speaks of heirs as remaining “under guardians and

trustees until the date set by the father” (Galatians 4:2). The image of the

child under “guardians and trustees” goes beyond the image of the paidagôgos because when a child reached

maturity and freedom they were free of the authority of the paidagôgos, but that did not mean they

were considered free adults or heirs to the property. Especially if the father

was dead, they would be placed under “guardians and trustees,” which could last

into a child’s twenties. Paul does not propose the “death” of God here,

naturally, but perhaps estrangement would be a proper way to speak of this need

for “guardians and trustees.” It might also be seen to connect with Paul’s

later language regarding adoption by God of the followers of Jesus into the family

of Abraham (and so God’s family). This raises the question of whether the

father from whom people are estranged is the same father who now adopts them, but

in Paul’s view this seems entirely possible to me.

Paul’s metaphor

continues, however, in an even more complex direction when he says that “so

with us; while we were minors (nêpioi

again, “infants”), we were enslaved to the elemental spirits of the world” (Galatians

4:3). It would seem that the law functioned

as a paidagôgos, a guardian and a

trustee, but now also “the elemental spirits of the world.” This is a strange verse, not because of the

imagery of the minor being “enslaved” - this is hyperbole as I mentioned, but

balanced by Paul’s contrast between being a minor and gaining freedom as an

adult heir in his earlier usage – but because of the use of stoicheia. Stoicheia

generally is thought to refer to the four elements of the world – earth, air,

water and fire – which were worshipped or considered by some in Paul’s day as

gods. If the Law of Moses is not here being considered as pagan gods, it seems

that such cosmic powers functioned as the equivalent of the law prior to the

coming of Jesus in Paul’s understanding. It is hard to believe many faithful

Jews of Paul’s day found this an acceptable equivalence.

Still, Paul’s multivalent

metaphor continues to build: “when the fullness of time had come, God sent his

Son, born of a woman, born under the law” (Galatians 4:4). The “fullness of time” is definitely a Jewish

religious notion, adopted by the early Christians, that since history is in

God’s hands, nothing occurs without God’s knowledge and functions as a part of

a “plan” for humanity. This biblical notion permeates all of Paul’s writings,

but is particularly powerful in this section of Galatians. The “fullness of

time” was that particular time when Jesus was sent, born as a Jew under the Law

of Moses, to allow for humanity to come to maturity. Particular is the key word

here, for it is the particularity of Jesus as a Jew which allows for humanity

to be adopted into the Abrahamic covenant.

Interestingly, to my

mind, Paul speaks of Jesus’ incarnation as allowing him “to redeem those who

were under the law, so that we might receive adoption as children” (Galatians

4:5). Interesting, since Jesus’ task was not simply to redeem those “under the

law,” but all humanity. Is this why, however, Paul has spoken of the stoicheia as an equivalent “enslaving”

force to the law, in order to include all of the nations? This seems probable to me, though since the

Galatians are enamored of the law, it could simply be that Paul wants to stress

that they, like the Jews and all others, are now free from it in their

maturity.

Though Paul has transitioned

here to some extent and returned to earlier issues and language- it is those

under the law who were in need of redemption, or freedom – there is no question

that freedom and redemption are intended for all humanity. In the same way, all are intended to gain

adoption as children. The word “adoption” (huiothesian,

“sonship” literally) reflects Greek conceptions

regarding adoption, since these were far more common practices in Greek and

Roman society.

The term huiothesian occurs only in Paul in the

NT. The use of huiothesian demonstrates

that the followers of Jesus have been adopted through divine initiative by God.

There are a number of aspects to this adoption, however, which must be

stressed. Though adoption was of sons almost without fail in Greece and Rome,

the language in Paul must refer to both males and females and might help to

make sense of Gal 3:27 that there is no longer male or female, slave or free,

Jew or Greek in the Church, for all are equal members of God’s family. Second,

adoption in Paul’s letters, especially Galatians and Romans, must be seen to

have two levels, namely, adoption into the family and lineage of Abraham and,

as a result, the adoption of this covenantal family into God’s family. Third,

such adoption is due to the son Jesus Christ, though it is not clear from

Greek, Roman or Jewish precedents how the natural son would be the means by which

others were adopted into a family. Most often it is the lack of a natural son

which leads to adoption, but in Paul’s understanding Jesus’ natural sonship is

what allows others to become sons and daughters of the father and heirs to his

promises. It is not clear what historical precedent there is for this

conception of adoption, apart from the covenantal language of Gen 15 and 17 in

which all one’s heirs become receivers of the lineage, but Paul speaks of the

“Spirit” as significant for such adoption.

This gets to the

heart of Paul’s language in Galatians 4:6-7, “And because you are children, God

has sent the Spirit of his Son into our hearts, crying, ‘Abba! Father!’ So you

are no longer a slave but a child, and if a child then also an heir, through

God.” It

is the experience of the Spirit, recall, which Paul wants to utilize to draw

the Galatians back to the Gospel in 3:1-5. Unless they had had this

experience of “adoption,” Paul could not utilize the image successfully. It is

this conformation to the Son, through the Spirit, a transformation only

completed at the eschaton, which allows Christians to be adoptive members of

God’s family. That is, it is the “Spirit

of his Son” which is transformative and allows all those who are Christians to

claim the membership as adopted children in God’s family. It is the cry of Abba

which points to the participation of Christians in the sonship of Jesus Christ,

since the phrase “Abba, Father” (abba ho

pater) is elsewhere found only in

Mark 14:36 on the lips of Jesus.

Next entry, more on the stoicheia.

John W. Martens

I invite you to follow

me on Twitter @Biblejunkies

I encourage you to

“Like” Biblejunkies on Facebook.

This

entry is cross-posted at America Magazine The Good Word

0 comments:

Post a Comment