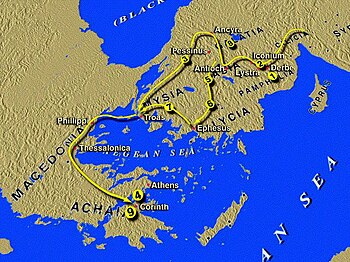

| English: Map of the Letters of Galatia (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

In

the first entry in the Bible Junkies Online Commentary on Galatians, I

discussed introductory matters concerning the founding of the churches to the

Galatians, the situation when Paul wrote to them, when the letter might have

been written and the type of letters which Paul wrote, based on the common

Greco-Roman letters of his day. In

the second post, I considered the basic content and breakdown of a Pauline

letter. I noted the major sections of the formal letter structure and, in the

context of each section, outlined the theological and ethical (as well as

other) concerns of Paul, including some Greek words which will be examined more

fully as we continue with the commentary. In

the third entry, I looked at the salutation, which is long for Paul’s

corpus (only Romans 1:1-7 is longer) and briefly commented on the lack of a

Thanksgiving, the only letter of Paul’s which does not have one. The

fourth entry discussed the opening of the body of the letter, a significant

part of the letter especially in light of the absence of a Thanksgiving.

4. Paul’s Letter to the Galatians

d) Body of the Letter (1:13-6:10):

i) Paul's Background in Judaism 1 (1:13-17):

13 You

have heard, no doubt, of my earlier life in Judaism. I was violently

persecuting the church of God and was trying to destroy it. 14 I advanced

in Judaism beyond many among my people of the same age, for I was far more

zealous for the traditions of my ancestors. 15 But when God, who had set

me apart before I was born and called me through his grace, was pleased 16 to

reveal his Son to me, so that I might proclaim him among the Gentiles, I did

not confer with any human being, 17 nor did I go up to Jerusalem to those

who were already apostles before me, but I went away at once into Arabia, and

afterwards I returned to Damascus. (NRSV)

In this section of

Galatians, Paul recalls his former manner of life as a persecutor of the

Church, who was called by revelation and grace to proclaim Jesus among the

Gentiles. This call was not dependent upon the previous Apostles, for the call

did not come from human authorities, not even Apostles, since Paul did not meet

them until years later (1:13-17).

Paul begins by

noting his “earlier life in Judaism” (τὴν ἐμὴν ἀναστροφήν ποτε ἐν τῷ Ἰουδαϊσμῷ-

tên emên anastrophên pote en tô Ioudaismô), which need not indicate that Paul

no longer considers himself a Jew, but the manner or type of life which he

formerly lived, since the point of the reminiscence is to recall the fact that

he was “violently persecuting the church of God and was trying to destroy it”

(1:13). Evidence of Paul’s persecution of the followers of Jesus also comes

from 1 Corinthians 15:9, Philippians 3:6, and Acts 8:3; this is an undeniable part

of Paul’s earlier religious life, but why? Why did Paul seek to destroy the “Church

of God”?

Paul speaks of

having “advanced in Judaism beyond many among my people of the same age, for I

was far more zealous for the traditions of my ancestors” (1:14). Richard Hays,

in the notes to the Harper Collins Study Bible, remarks that “advanced” (proekopton) was a “word commonly used by

Stoic philosophers to describe progress in cultivating virtue” (1974) and I

think that whether one sees specific Stoic influence here, which is possible,

it is important to see that Paul understands his previous persecution of the

Church in a religious light. He links his persecution with his being “zealous”

for the “traditions of my ancestors” (1:14).[1]

How could

persecution of other Jews be linked to progress in virtue? The word “zealous”

is key as is the phrase “traditions of my ancestors.” Both can be linked to

Paul’s life as a Pharisee. “Traditions of my ancestors” describes the oral

traditions regarding the Law of Moses and the “strict” (akribeia) interpretations of those laws practiced by the Pharisees

(see A. I. Baumgarten, “The Name of the Pharisees” in JBL 102 (1983) 413-17). As a result of these “strict”

interpretations of the law, many people were considered by the Pharisees not to

have properly followed or fulfilled the requirements of the law even though

these same people would have seen themselves as loyal Jews.

It can also be said,

as Paul himself does, that to be a “strict” interpreter of the law was to be “zealous”

for the law (see also Philippians 3:6). To be zealous for the law had a long

pedigree in Judaism prior to Paul. The key passage and incident is that of

Phinehas in Numbers 25:6-13, in which a Midianite woman and the Israelite who

brought her into his tent are slain by Phinehas due to his zeal for the law. There

are many other examples of “zealousness” from which to choose in the biblical

tradition (see James Dunn, Jesus,

Paul and the Gospels Eerdmans: 2011, 150-52), but that of Mattathias in

1 Maccabees 1-2 is most relevant. Not only does Mattathias call upon the memory

of Phinehas when slaying the representative of Antiochus Epiphanes and a Jew

who was to make an idolatrous sacrifice (1 Maccabees 2:23-26), but to be “zealous”

for the law is the condition of opposing the persecutions of Antiochus

Epiphanes for those who would join Mattathias (1 Maccabees 2:27) and a

characteristic of those Israelite heroes who had defended the faith before

Mattathias (1 Maccabees 2:51-60).

Some scholars have

even located the origins of the Pharisees in the Maccabean revolt, tracing the Pharisees

to the “Hasideans” (Hasidim) or “pious ones,” who join with Mattathias and his

sons to oppose the persecution of Antiochus Epiphanes. They are called “mighty

warriors of Israel, all who offered themselves willingly for the law” (1

Maccabees 2:42). Whether this is the precise group from whom the Pharisees grew,

and there is little evidence for this,[2]

it is generally the belief that the Pharisees did emerge from the fulcrum

of ideas and responses to the persecutions of Antiochus Epiphanes and the

response of the Maccabeans in the Hellenistic period, if not earlier. The first

reference to the Pharisees places them in the reign of the Hasmonean John

Hyrcanus (134-104 B.C.E.) (Josephus,Ant13.10.5). Since the

Pharisees do emerge only after the Maccabean revolt, and with a strong OT

pedigree to support them, zealousness for the law becomes a watchword for their

love of the Torah and desire to protect it from persecution and ignorance, such

as that of the Antiochean persecution. Faithful Jews in the later Hellenistic

and Greco-Roman periods would support this position in a variety of ways, such

as the “Zealots,”

who oppose with force Roman rule, but they key was to protect the Torah and the

practice of Judaism.

Paul is a part of

this history and his persecution of the Church is an attempt to rid Judaism of

what he saw as a sadly misguided reformation or interpretation of Judaism. We

are unclear, though, on whether his persecution was a response to Jesus’ own

teachings on the Torah – if Paul even knew of them – or whether it is a

response to the practices or beliefs of Jesus’ followers and their

interpretation of the Law of Moses, or whether he disapproved of their claim

that Jesus was the Messiah.

Paul’s turn away

from persecution and to Jesus comes through the revelatory experience he

mentioned in Galatians 1:12 and further outlines in 1:15-16a, “when God, who

had set me apart before I was born and called me through his grace, was pleased

to reveal his Son to me.” Paul places himself here in the role of the prophet

whom God calls even before birth (Jeremiah 1:5; Isaiah 49:1-6) and in the

constant sense of grace which he has experienced through Christ. Paul now sees

Jesus and himself as part of God’s revelation to the Jews not in opposition to

it. Again, Paul notes that God was pleased “to reveal” (apokalypsai) “his Son” to him, which points to a complex spiritual

experience that turned Paul’s life around. Whatever one thinks of religious

experience as a category, or the content of mystical experiences, Paul’s “revelation”

turns him from persecution of the Church to the Church’s major proponent, from being

willing to harm others on account of their faith in Christ to being willing to

be harmed for the Gospel and his faith in Christ.

Something real

happened to Paul through his encounter with God’s son who was revealed “in me”

(en emoi). This is translated usually

as “to me,” as in the NRSV, which is grammatically possible and

probably even likely, but “through me” is also possible (on these grammatical

questions see Joseph Fitzmyer, S.J., New Jerome Biblical Commentary,

Galatians 47:16, 783). I like “through me,” which fits with the task Paul was

given in 1:16b, but Fitzmyer finds it “redundant” in light of that task. What we

can say, I think, is that every aspect of this preposition is in play here: God’s

son was revealed in, to and through Paul for the purposes of making the Gospel

known to the nations. Paul is the means by which Jesus is proclaimed.

Finally, Paul

stresses again that “I did not confer with any human being, nor did I go up to

Jerusalem to those who were already apostles before me, but I went away at once

into Arabia, and afterwards I returned to Damascus” (1:16b-17). This repeated emphasis

is to indicate that Paul’s Gospel is divine in origin, as has already been seen

earlier in Galatians 1 (see entry

four), and we will examine the implications of this declaration for his

relationship to the Gospel he preaches and his relationship with the Church and

the Apostles in particular in the next two entries. As to Paul’s journey to

Arabia, this has generally been considered to be the Nabatean kingdom of Aretas

IV Philopatris, which was south of Damascus and east of the Jordan River (see 2

Corinthians 11:32), though this is not certain. What it does indicate is that Paul

did not consult with the Apostles, but retreated to commune with God or with

other Christians unknown to us.

Next entry, Paul travels to Jerusalem to meet the Apostles.

John W. Martens

I

invite you to follow me on Twitter @Biblejunkies

I

encourage you to “Like” Biblejunkies on Facebook.

This entry is cross-posted at

America Magazine The Good Word

[1]

“Ancestors” here is a translation of patrikôn,

which is more literally, and probably in a 1st century context more

accurately, “fathers.”

[2]

See Shaye, J.D. Cohen, From

the Maccabees to the Mishnah (Westminster John Know Press: 2006) 154-55

who sees “little evidence” for this connection. For a fascinating survey by the

same author on the purported connections between the Pharisees and the later

Rabbis and the Rabbinic desire for later Judaism not to represent the sectarian

nature of the Pharisees see “The

Significance of Yavneh: Pharisees, Rabbis, and the End of Jewish Sectarianism”

now in The Significance of Yavneh and Other Essays in Jewish Hellenism (Mohr Siebeck: 2010)

0 comments:

Post a Comment