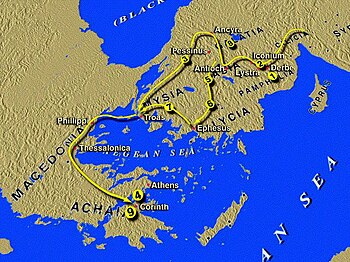

| English: Map of the Letters of Galatia (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

|

| St. Paul Outside the Walls, Rome. |

The fifth Bible Junkies Commentary, which begins with this

post, is a study of Paul’s powerful letter to the Galatians. This letter has

been significant throughout Christian history, but it took on a pronounced and

central role during the Protestant Reformation due to Martin Luther’s focus on “faith,”

“works” and the central concept of “justification” in this letter. Indeed, I

will engage with Luther’s own commentary on Galatians at times, not simply

because I take positions contrary to his but because it is best to go the

source and allow him to speak for himself. This does not mean, though, that my

approach will be to pit “Catholic” and “Protestant” readings of Galatians

against one another; rather my approach will be to rely on the best current scholarship

on Galatians available and to situate Galatians in its early Christian and

Jewish context to best understand the concrete situations among the Galatians,

their relationship with Paul the Apostle, and the theological issues that

resulted in this letter.

1)

Salutation (name(s) of writer(s) and recipient(s); greeting)

2)

Thanksgiving

3)

Body of the Letter

4)

Closing: greeting.

1)

Salutation (name(s) of writer(s) and recipient(s); greeting)

2)

Thanksgiving

3)

Opening of the Body of the Letter

4)

Body of the Letter (usually in two parts, theoretical and practical)

5)

Closing of the Body of the Letter (often with the promise of a visit)

6)

Ethical Instructions (‘Paraenesis’)

7)

Closing: greetings; doxology; benediction (John Ziesler, Pauline Christianity, 7)

1)

Salutation: a) sender; b) recipient; c) greeting

2)

Thanksgiving: (Prayer)

3)

Body of the Letter (Paraenesis: Ethical Instruction and Exhortation)

4)

Closing commands

5)

Conclusion: a) peace wish; b) greetings; c) kiss; d) close (grace; benediction)

(Calvin Roetzel, The Letters of Paul:

Conversations in Context, 53-54)

1) Salutation: a) sender; b)

recipient; c) grace;

2) Thanksgiving: This often

contains intentions for the entire letter and a prayer for the recipients;

3) Body of the

Letter: often contains two parts, though not necessarily neatly divided:

a) theological teaching and instruction, especially regarding errors in belief

and practice; b) Paraenesis: Ethical Instruction and Exhortation;

4) Closing of the

Body of the Letter: Closing commands, often with

the promise of a visit and greetings;

5) Closing: Conclusion might

contain some or all of these elements: a) peace wish; b) greetings; c) kiss; d)

close (grace; doxology; benediction) (Roetzel, 53-54;Ziesler, 7)

2. The Background to Paul’s Activity in Galatia

Proponents of the S. Galatia theory hold that the letter is directed to churches found in the Roman province and mentioned in Acts 13:14-14:23, such as Antioch in Pisidia, Lystra and Derbe. These scholars equate the journey to Jerusalem described by Paul in Galatians 2:1-10 with that mentioned, briefly, in Acts 11:29-30. This would explain the absence of the “apostolic decrees” in the letter to the Galatians, those decrees formulated by the Jerusalem council concerning fornication, meat offered to idols, etc. and mentioned in Acts 15:20 and 29, since the assumption would be that Galatians was written before the Jerusalem council took place. Since the council took place around 50 C.E., the letter to the Galatians would have an early date in the late 40's. This would make this letter about as early as the first letter to the Thessalonians.

Those who follow the N. Galatia hypothesis sees the

recipients as the actual Galatian tribes, the churches of the descendants of

the Gauls or those churches in the actual Galatian tribal territory. The

journey to Jerusalem which Paul describes in Gal. 2:1-10 is correlated with the

journey of Paul and Barnabas outlined in Acts 15. Exponents of this view tend

to date the letter to a later time frame, such as 55 C.E. or even to 57 C.E. I follow

the N. Galatia hypothesis and do think that the letter is written to “Galatians.”

Paul speaks of them as “foolish Galatians” (3:1), a linguistic usage which

indicates a “people” distinct from other peoples, though this need not imply

that everyone who belonged to the Galatian churches was an actual Gaul. The

problem for this hypothesis is why Paul does not mention the “apostolic decrees”

of Acts 15 in Gal. 2:1-10 and in fact says in Gal. 2:10, “they asked only one

thing, that we remember the poor, which was actually what I was eager to do.” A

supporter of the N. Galatia hypothesis will have to answer why Paul ignores

these decrees in a letter written some years after he attended the council of

Jerusalem.[1]

C) The Situation in Galatia:

Paul is passionately and sometimes

angrily defending his ministry and Gospel to the Galatians in this

letter. There are clearly “opponents” whom Paul is addressing, people who have

come from the “outside” (Galatians 17, 5:10, 12). These people have come to the

Galatian churches arguing for observance of Judaic practices, that is, the Law

of Moses, as necessary for salvation; the shorthand for this in Paul’s letter is

“circumcision.” Who are these “opponents”?

Without question these opponents were, like Paul himself,

Jewish Christians, but these Jewish Christians believed that it was essential

that all Christians, Jewish or Gentile, continue to follow the Law of Moses. They

did not believe that the coming of the Messiah indicated that the Law of Moses

was no longer valid; they either did not know of the Jerusalem council (or,

some might argue, the council had not yet taken place) or they ignored its

decrees, which is more likely, since the decrees of the Jerusalem council did

have strong opposition as seen in Acts 15:1, 5.

The opponents in Galatians are probably those Christians we

see in Acts 15 opposed to the council’s decisions, or aligned with them, and

who rejected a mission to the Gentiles without the Torah. They also attempt to

discredit Paul himself as an apostle, which is why Paul finds it essential to

defend not just his Gospel but himself (Galatians 1:1, 11-12). Paul denies in Galatians

that by arguing for the sufficiency of Christ he is at odds with the promises

of God to the Jewish people.

E) Place: If one supports the S.

Galatia hypothesis and so an earlier date for the letter, the probable place of

writing would be Corinth. If one follows the N. Galatia hypothesis and so a

later date for the letter, the most likely place would be Ephesus or Corinth.

Next entry, we begin to look at the content of the letter.

John W. Martens

I

invite you to follow me on Twitter @BiblejunkiesI encourage you to “Like” Biblejunkies on Facebook.

This entry is cross-posted at AmericaMagazine The Good Word

[1]

The N. Galatia hypothesis, which I support, is the most dominant view among

scholars today, but see Michael Gorman, Apostle

of the Crucified Lord, 184-86, for a defense of the S. Galatia hypothesis.

0 comments:

Post a Comment