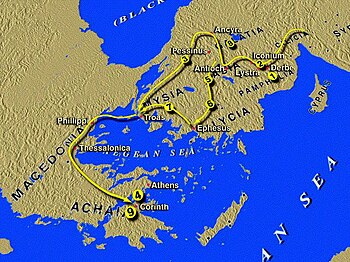

| English: Map of the Letters of Galatia (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

In

the first entry in the Bible Junkies Online Commentary on Galatians, I

discussed introductory matters concerning the founding of the churches to the

Galatians, the situation when Paul wrote to them, when the letter might have

been written and the type of letters which Paul wrote, based on the common

Greco-Roman letters of his day. In

the second post, I considered the basic content and breakdown of a Pauline

letter. I noted the major sections of the formal letter structure and, in the

context of each section, outlined the theological and ethical (as well as

other) concerns of Paul, including some Greek words which will be examined more

fully as we continue with the commentary. In

the third entry, I looked at the salutation, which is long for Paul’s

corpus (only Romans 1:1-7 is longer) and briefly commented on the lack of a

Thanksgiving, the only letter of Paul’s which does not have one. The

fourth entry discussed the opening of the body of the letter, a significant

part of the letter especially in light of the absence of a Thanksgiving. In

the fifth entry, I examined the beginning of the opening of the body of the

letter, in which Paul describes his background in Judaism and I placed this in

the context of Judaism in the Hellenistic period. In the

sixth post in the online commentary, I continued to look at Paul’s

biographical sketch of his life, this concerning his earliest life as a

Christian. In

the seventh post, I examined what Paul says about his subsequent visit to

Jerusalem to see the apostles and the Church in Jerusalem.

In the eighth entry, Paul confronts Cephas (Peter) about his hypocrisy in Antioch.

The ninth blog post, offered below, begins to examine the

theological argument in one of Paul’s most important and complex theological

letters.

4. Paul’s Letter to the Galatians

d) Body of the Letter (1:13-6:10):

iv) Theological Teaching (2:15-5:12): Jews

and Gentiles “justified” by Christ (2:15-21).

15 We ourselves

are Jews by birth and not Gentile sinners; 16 yet we know that

a person is justified not by the works of the law but through faith in Jesus

Christ. And we have come to believe in Christ Jesus, so that we might be

justified by faith in Christ, and not by doing the works of the law, because no

one will be justified by the works of the law. 17 But if, in

our effort to be justified in Christ, we ourselves have been found to be

sinners, is Christ then a servant of sin? Certainly not! 18 But

if I build up again the very things that I once tore down, then I demonstrate

that I am a transgressor. 19 For through the law I died to the

law, so that I might live to God. I have been crucified with Christ; 20 and

it is no longer I who live, but it is Christ who lives in me. And the life I

now live in the flesh I live by faith in the Son of God, who loved me and gave

himself for me. 21 I do not nullify the grace of God; for if

justification comes through the law, then Christ died for nothing.

(NRSV)

At the beginning of

this section, in Galatians 2:15, Paul says to Peter that “we ourselves are Jews

by birth and not Gentile sinners.” The word translated as “by birth” is physei, which literally means “by

nature.”[1]

The translation, it seems to me,

is fine as it indicates that Paul and Peter share this “natural condition” (as

Joseph Fitzmyer puts it, NJBC, 784)

by virtue of origin. It is a subtle rhetorical technique that Paul uses,

aligning himself with Peter, and by extension his opponents in Galatia, by

putting them all on the same “team.” Paul then contrasts his “team” with the

“Gentile sinners,” a common attitude among many Jews in antiquity. By

definition, one could consider Gentiles “sinners,” since they did not live

according to God’s Law, that given to Moses and contained in the Torah. Paul

places himself and those with whom he is debating on an even field and then

tilts the field by bringing in the game-changer: Jesus.

Paul undermines the

advantage of birth that he and Peter shared by stating that “we know that a

person is justified not by the works of the law but through faith in Jesus

Christ” (Galatians 2:16a). Once again, Paul has aligned Peter with him, but in

this case to challenge Peter’s behavior in Antioch and to demonstrate how

theologically unsound it is to divide Christians into categories such as Jew

and Gentile. Paul has said a mouthful, though, in such a short space, speaking

of justification, works of the law and faith in Jesus Christ. Some preliminary work

is needed on each of these topics.

“A person is

justified” (dikaioutai) says Paul,

but what is the general meaning of this verb dikaioô? What does it mean to be “justified? This Greek verb and associated nouns

originally referred to “justice” and the results of justice delivered – a just

verdict – in a court of law. In this use it has a legal sense of being

acquitted. We can speak of this usage as “forensic.” In its use in Judaism (the

Septuagint - LXX), it came also to mean “righteousness,” especially as it

related to the keeping of God’s Law. Paul’s use of this group of words takes us

in a new direction, though obviously related to its use in Greek and Jewish

settings.

The first and basic

issue is anthropological: human beings find themselves as sinful before God.

What can repair this situation or relationship? For Paul, you are not justified

“by the works of the law but through faith in Jesus Christ.” It is through

Christ’s passion, death, and resurrection, and our participation in it, through

baptism and a life of holiness, that we become “justified.” As a result, those

who participate can “now stand before God’s tribunal acquitted or innocent” (NJBC, 1397; Rom. 4:25).

What allows one to

be justified? Paul states that one is justified “through faith in/of Christ.” I

use both prepositions, in and of, here to speak of “faith” with

respect to Christ because there is a debate whether Paul’s use of pisteôs Iesou Christou refers to the

subjective genitive (faith of Christ)

or objective genitive (faith in Christ).

I do not want to (try to) settle this debate here, but to consider this over

the next few posts. There are good arguments on both sides, but the primary

issue is whether it is Christ’s faith(fulness) that saves us or the Christian’s

faith in what Christ has accomplished. In one case the accent is on the person

(objective) and in the other on Christ (subjective), but it is important to

acknowledge that it is Christ who saves in Paul’s soteriology regardless of how

this phrase is translated.

Now it is true that the

action whereby God “justifies” the sinner has been the subject of much debate. Since

the Protestant reformation, Martin Luther, and others, have argued that

“justification by faith” means that we add nothing to what God through Christ

has gained for us, not that in other areas good works and charity might not be

discussed, but that when we speak of justification there is nothing to be added

beyond our faith in Christ (objective genitive). In his A Commentary on St. Paul’s Epistle to the Galatians, Luther writes

“here we must stand, not upon the wicked gloss of the schoolmen, which say,

that faith then justifieth, when charity and good works are joined withal” (WA

401, 238, 30). Catholics, of course, affirm that what Christ has

done for us is “by faith,” that there is nothing we can do to earn this gift

gained “through faith in/of Christ,” but that the language of justification

involves not just a “forensic” declaration, but a “causative” or “factitive” or

“transformative” dimension in which the Christian necessarily participates.

Paul speaks of

righteousness as not now based upon one’s one observance of the Law of Moses,

by fulfilling the works it prescribes – this is what Paul means by the phrase

“works of the Law”- but by a participation in God’s righteousness through faith

in Christ. As such, it is justification gained by divine intervention. “It is

known by its manifestations, because it is essentially active, dynamic,

communicating benefits proper to God, making, as it were, a new creation (2

Cor. 5:17); and its goal is the justification of humans (Rom. 3:25-26)” (Ceslas

Spicq, Theological Lexicon of the New

Testament, 335). This justification, though, is not a simple acquittal, but

it “transforms the one who participates in Christ’s death and resurrection”

(Spicq, 335). Faith and justification must also be distinguished: “it is not

faith that justifies, but God who justifies through faith. In faith, a person

appropriates Christ’s righteousness (Gal. 2:17, the efficient cause of our own righteousness, thus

becoming the “righteousness of God,” 2 Cor. 5:21)” (Spicq, 336). While a person is justified “by means

of faith,” the principal agent is God.

Understood in this

way, to be righteous or just by faith is not simply “forensic” – a legal

declaration made of the person who accepts Christ, but fictive in that it

states what is without transforming the person – but to be transformed by God,

as a process whose end is our sanctification. This is the major difference

regarding justification between Catholics and Protestants, particularly

Lutherans, who see righteousness as primarily “forensic” or “declarative,” but

not “transformative” or “causative.”

And yet, note where

we are now: in the midst of discussions and language which arose in the 16th

century. Paul did not live in the 16th century, he lived in the 1st

century and he never heard of “schoolmen” or Martin Luther. This is not to

dismiss the debates of the 16th century or their continuing

importance, but to take us back to Paul’s own day. What did Paul mean by “works

of the Law”? Did Jews of Paul’s day believe that one was saved by performing

“works of the Law”? Does Paul represent his compatriots fairly? This was at the

heart of E.P. Sanders’ re-evaluation of these debates in Paul

and Palestinian Judaism in which he argued that we had foisted later

Christian disputes regarding faith and works on Paul. Sanders spoke of

“covenantal nomism” as the means by which Jews of Paul’s day understood their

relationship to God. Jews were required to perform the works of the Law to

remain in the covenant, but the covenant was a gracious gift of God. Sanders

believes that Paul’s major concern was whether one still entered the covenant

on ethnic grounds or whether entry into the covenant was expanded to Gentiles

who entered through “faith in/of Jesus Christ.” Christians would still have to

behave in certain ways to remain within the covenant/Church, but salvation came

not through these ways of behaving, but through Christ. It is with Sanders that

scholars date the beginning of the “New Perspective” on Paul, to which we will

return in later posts.

Paul says in

Galatians 2:16b that “we have come to believe in Christ Jesus,[2]

so that we might be justified by faith in Christ, and not by doing the works of

the law, because no one will be justified by the works of the law.” All of the

language from 2:16a is repeated here. Note again that justification refers to

being found righteous before God, being acquitted, and it is on the basis of

faith, not the works of the Law (of Moses), that one is found righteous Paul

says. We have to ask ourselves: is this a faith versus works argument? Or an

argument that it is through faith in Christ that entry into the covenant is

gained for Gentiles (and Jews) not through the Law of Moses, which divided Jew

from Gentile?

Paul then asks in

Galatians 2:17 whether “if, in our effort to be justified in Christ, we

ourselves have been found to be sinners, is Christ then a servant of sin?

Certainly not!” The sense of “sinner” here must be that as in 2:15, “Gentile

sinners.” Paul is deconstructing the very notion that Gentiles are by nature

sinners since with the coming of Christ it is faith in Christ not having the

Law of Moses which justifies; as such Christ cannot be a servant or an agent of

sin even if certain laws regarding food are being cast aside. In fact, Paul

says, “If I build up again the very things that I once tore down, then I demonstrate

that I am a transgressor” (Galatians 2:18). If Paul was to reintroduce the

distinctions between Jews and Gentiles, he argues, he would be the one at

fault.

Paul has moved the

argument to the point that the Law of Moses is no longer the measuring stick

for a Christian, and even more “through the law I died to the law, so that I

might live to God. I have been crucified with Christ; and it is no longer I who

live, but it is Christ who lives in me. And the life I now live in the flesh I

live by faith in the Son of God, who loved me and gave himself for me”

(Galatians 2:19-20). Jesus is not a servant of sin (2:17) and Paul is not a

transgressor (2:18): why? By following Jesus Paul has “died to the law” and he

has been “crucified with Christ.” This might mean that Christ has fulfilled the

law (as in Galatians 5:14; see also Romans 8:4), or that Christ is the end of

the law (Romans 10:4), but it also points to a nearby verse, Galatians 3:13,

wherein Paul says “Christ redeemed us from the curse of the law.” The important

thing to recognize here is that Paul sees Christ as bringing the significance

of the law as a standard to an end so that in Christ “I might live to God.” And

Paul sees this life as Christ living in him. This does speak against, it seems

to me, justification as a merely “forensic” declaration, but as a

transformative experience of the person who now lives mystically, somehow, with

Christ.

Finally, Paul says

that “I do not nullify the grace of God,” which must be a challenge for those,

like Peter and the interlopers, who have turned away from Gentiles in table

fellowship and perhaps in other ways. Paul’s behavior is aligned, that is, with

God’s grace not in opposition to it like the others, who, we are to understand,

are nullifying God’s grace. The last phrase “for if justification comes through

the law, then Christ died for nothing” is the phrase that one can continue to

come back to over and over again when Galatians gets too confusing (or when the

commentators get too confusing). It succinctly gives the reason for Paul’s

behavior and the reason for his new path: the Law of Moses was God’s way, but

then he sent Christ to die and Paul had an encounter with the Risen Lord. If

nothing was to change, why did God send Jesus to die? [3]

Next entry, more on Law or faith in Christ?

John W. Martens

I

invite you to follow me on Twitter @Biblejunkies

I

encourage you to “Like” Biblejunkies on Facebook.

This entry is cross-posted at

America Magazine The Good Word

[1]

It is the dative of the noun physis,

“nature.”

[2]

It is important to point out also that

the verb translated as “believe” in 2:16b is episteusamen, which is a form of pisteuô, a verb that can be translated as “to have faith.” Remember

the noun for faith is pistis. This is

an argument, I would suggest, for the objective genitive reading of “faith

in/of Christ,” for it is clear that the accent is on the subject “we,” as in,

“we have come to have faith in Christ Jesus.”

[3]

I must, though, muddy the waters a bit,

for the word dôrean is a little

difficult to figure out. The phrase reads, “for if justification comes through the law, then Christ died dôrean.” Dôrean most often means “gift,” but it would be strange to see the

phrase meaning Christ “died (as) a gift,” unless it indicates a gift which was

unnecessary or unwanted or unused. As a result, the translations tend to settle

on the translation “for nothing,” by which is meant “for no reason” or “for no

purpose.”

0 comments:

Post a Comment