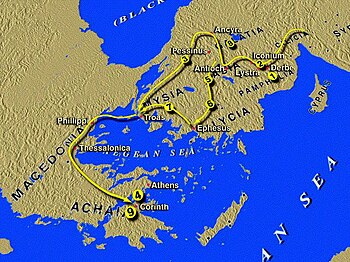

| English: Map of the Letters of Galatia (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

In

the first entry in the Bible Junkies Online Commentary on Galatians, I

discussed introductory matters concerning the founding of the churches to the

Galatians, the situation when Paul wrote to them, when the letter might have

been written and the type of letters which Paul wrote, based on the common

Greco-Roman letters of his day. In

the second post, I considered the basic content and breakdown of a Pauline

letter. I noted the major sections of the formal letter structure and, in the

context of each section, outlined the theological and ethical (as well as

other) concerns of Paul, including some Greek words which will be examined more

fully as we continue with the commentary. In

the third entry, I looked at the salutation, which is long for Paul’s

corpus (only Romans 1:1-7 is longer) and briefly commented on the lack of a

Thanksgiving, the only letter of Paul’s which does not have one. The

fourth entry discussed the opening of the body of the letter, a significant

part of the letter especially in light of the absence of a Thanksgiving. In

the fifth entry, I examined the beginning of the opening of the body of the

letter, in which Paul describes his background in Judaism and I placed this in

the context of Judaism in the Hellenistic period. In the

sixth post in the online commentary, I continued to look at Paul’s

biographical sketch of his life, this concerning his earliest life as a

Christian. In

the seventh post, I examined what Paul says about his subsequent visit to

Jerusalem to see the apostles and the Church in Jerusalem.

In the eighth entry, Paul confronts Cephas about his hypocrisy in Antioch.

The

ninth blog post started to examine the theological argument in one of

Paul’s most important and complex theological letters. In

the tenth entry, Paul makes an emotional appeal to the Galatians based on

their past religious experiences and their relationship with Paul. In this, the

eleventh chapter in the series, Paul begins to examine Abraham in light of his

faith.

4. Paul’s Letter to the Galatians

d) Body of the Letter (1:13-6:10):

iv) Theological Teaching (2:15-5:12): Abraham

was justified by faith (3:6-9) part 1.

6

Just as Abraham “believed God, and it was reckoned to him as righteousness,” 7

so, you see, those who believe are the descendants of Abraham. 8 And the

scripture, foreseeing that God would justify the Gentiles by faith, declared

the gospel beforehand to Abraham, saying, “All the Gentiles shall be blessed in

you.” 9 For this reason, those who believe are blessed with Abraham who

believed. (NRSV)

Paul’s concern in contrasting “works of the Law” and “faith in Christ,” as

he does in Galatians 2, does not have to do with a consideration of

“legalism” as a central part of Judaism, or even less “works righteousness,” but

in Paul wrestling with the reality of his encounter with Jesus Christ. In this

revelation, and subsequent Christian teaching and reflection, Paul came to

understand that justification was found through Christ. Whenever one is lost in

Galatians, it is good to go back to Galatians 2:21: “I do not nullify the grace

of God; for if justification comes through the law, then Christ died for

nothing.” This verse is Paul’s touchstone. Paul’s concerns have less to do with

the Law of Moses than with the meaningfulness of Christ’s death. As E. P

Sanders famously said of Paul’s soteriology, “the solution preceded the problem.”

Paul’s revelatory experience exposed an issue with which he was previously

unaware: if justification comes through Jesus Christ, what place does the Law

have in this new reality? Since Paul understood that God gave the Law to the

Israelites, he is bound to its divine origin and purpose, but what purpose does

it have now?

I think, in addition, there is another issue with which Paul is wrestling

in this letter and that might be termed a sociological one, namely, the place

of the Gentiles, or the nations, in salvation history. If justification comes

through Christ for all people and if the Law separated Jew from Gentile, as it

was intended to do in ways both profound and ordinary, what role would or could

the Law play in the life of the Church? I do not mean to deny the theological importance

of Paul’s musings, but whether Jews and Gentiles would eat together had

significant implications sociologically for the life of the Church.

Paul turns to Genesis for answers, particularly Genesis 12 and 15, and

builds his arguments on the person of Abraham. There are positive reasons for

doing this, which we will soon explore, but there might be defensive reasons

for drawing on Abraham as well. The interlopers with whom Paul is at odds must

certainly be drawing on Abraham too in their arguments with the Galatians and

the need to follow the Law of Moses. Now, it is true, that Abraham has not been

given the Law, but he is told by God in Genesis 17:9-14,

9…”As

for you, you shall keep my covenant, you and your offspring after you

throughout their generations. 10 This is my covenant, which you shall keep,

between me and you and your offspring after you: Every male among you shall be

circumcised. 11 You shall circumcise the flesh of your foreskins, and it shall

be a sign of the covenant between me and you. 12 Throughout your generations

every male among you shall be circumcised when he is eight days old, including

the slave born in your house and the one bought with your money from any

foreigner who is not of your offspring. 13 Both the slave born in your house

and the one bought with your money must be circumcised. So shall my covenant be

in your flesh an everlasting covenant. 14 Any uncircumcised male who is not

circumcised in the flesh of his foreskin shall be cut off from his people; he

has broken my covenant.”

Certainly, if I was in dispute with Paul, I would draw on this passage to

make my point that circumcision is essential for entry into the covenant. Even

if the Law was given later, circumcision remained the means by which males were

brought into the covenant.

Paul does not cite this passage, though, but turns to other events that

reflect God’s emerging covenantal relationship with Abraham. Paul cites Genesis

15:6 in Galatians 3:6, “just as Abraham ‘believed God, and it was reckoned to

him as righteousness’.” This is key for Paul because in the LXX (Septuagint –

the Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures), the verb “believed” is episteusen, a form of pisteuô. As

we have seen, pistis is the noun

for “faith” and pisteuô the verb,

which might be translated as “have faith.” Paul, that is, is consistent in his

language in Greek and “faith” is at the basis of his argument even when drawing

on Abraham in Genesis. Even before God gave the Law to Moses, even before

circumcision, God reckoned Abraham’s faith as “righteousness” (dikaiosynê). Recall

again, that the Greek verb dikaioô,

often translated as “justified,” is the same root that gives us the noun dikaiosynê, which could be translated

“righteousness” or “justification,” and other related nouns. Paul, therefore,

is consistently using the same root-stem nouns and verbs for the words we

translate variously as “believe” and faith” or “righteousness” and “justified.”

He is consistent in his usage and his usage is based upon the LXX.

On the basis of this verse, though, Paul feels comfortable to say that “those

who believe are the descendants of Abraham” (Galatians 3:7). The

actual phrase in Greek recalls Galatians 3:2 and 3:5, in which Paul said

the Galatians had received the Spirit ex

akoês pisteôs, that is, “believing what you heard” or more literally “having

faith in what you heard.” In 3:7 Paul says hoi

ek pisteôs, “those out of faith,” or “those who believe” are huioi (literally: “sons”) of Abraham,

which is a negation of lineage according to national identity. The phrase ek pisteôs is identical to that found in

3:2, 5 (ex is the same preposition as

ek, but the consonant changes due to

the appearance of a vowel before it). Faith, for Paul, is now not just how the

Galatians received the Spirit, based in their experience, but how Abraham himself,

the father of Israel, entered into the covenant with God.

Paul pushes his argument farther

even, stating that “the scripture, foreseeing that God would justify the

Gentiles by faith, declared the gospel beforehand to Abraham, saying, “All the

Gentiles shall be blessed in you” (Galatians 3:8). Drawing again on Genesis, in

this case LXX Genesis 12:3, Paul understands that this passage was pointing

forward to Christ’s coming and the entry of the nations into the covenant by

faith. Paul again uses words with which we should now be comfortable: ek pisteôs is here translated as “by

faith” while “justify” is dikaioi.

Gentiles is a key word and in Greek it is ethnê,

from which we derive variations on “ethnic.” It simply means “the nations,”

what would be goyim in Hebrew. So,

Paul sees Scripture not just pointing to “faith” as the means by which one

would be declared righteous or “justified,” just as Abraham was, but the means

in the future by which all the nations of the world would someday be “justified.”

That is, justification was foreseen as a means of entering into relationship

with God which transcended national boundaries.

And so Paul concludes this short historical and scriptural survey,

stating “for this reason, those who believe are blessed with Abraham who

believed” (Galatians 3:9). It will be no surprise that “those who believe” translates

hoi ek pisteôs (as in Galatians 3:7)

and Abraham “who believed” is derived from syn

tô pistô. As Abraham had faith, and was blessed, so those who have faith,

Paul says, are blessed with him, even those who have faith now.

Next entry, more on the model of Abraham and Paul’s Midrash

on Scripture

John W. Martens

I

invite you to follow me on Twitter @Biblejunkies

I

encourage you to “Like” Biblejunkies on Facebook.

This entry is cross-posted at

America Magazine The Good Word

0 comments:

Post a Comment