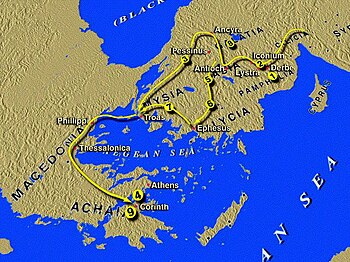

| English: Map of the Letters of Galatia (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

In

the first entry in the Bible Junkies Online Commentary on Galatians, I

discussed introductory matters concerning the founding of the churches to the

Galatians, the situation when Paul wrote to them, when the letter might have

been written and the type of letters which Paul wrote, based on the common

Greco-Roman letters of his day. In

the second post, I considered the basic content and breakdown of a Pauline

letter. I noted the major sections of the formal letter structure and, in the

context of each section, outlined the theological and ethical (as well as

other) concerns of Paul, including some Greek words which will be examined more

fully as we continue with the commentary. In

the third entry, I looked at the salutation, which is long for Paul’s

corpus (only Romans 1:1-7 is longer) and briefly commented on the lack of a

Thanksgiving, the only letter of Paul’s which does not have one. The

fourth entry discussed the opening of the body of the letter, a significant

part of the letter especially in light of the absence of a Thanksgiving. In

the fifth entry, I examined the beginning of the opening of the body of the

letter, in which Paul describes his background in Judaism and I placed this in

the context of Judaism in the Hellenistic period. In the

sixth post in the online commentary, I continued to look at Paul’s

biographical sketch of his life, this concerning his earliest life as a

Christian. In

the seventh post, I examined what Paul says about his subsequent visit to

Jerusalem to see the apostles and the Church in Jerusalem.

In the eighth entry, Paul confronts Cephas about his hypocrisy in Antioch.

The

ninth blog post started to examine the theological argument in one of

Paul’s most important and complex theological letters. In the tenth entry,

found below, Paul makes an emotional appeal to the Galatians based on their

past religious experiences and their relationship with Paul.

4. Paul’s Letter to the Galatians

d) Body of the Letter (1:13-6:10):

iv) Theological Teaching (2:15-5:12): How did

you receive the Spirit? (3:1-5).

1

You foolish Galatians! Who has bewitched you? It was before your eyes that

Jesus Christ was publicly exhibited as crucified! 2 The only thing I want to

learn from you is this: Did you receive the Spirit by doing the works of the

law or by believing what you heard? 3 Are you so foolish? Having started with

the Spirit, are you now ending with the flesh? 4 Did you experience so much for

nothing?—if it really was for nothing. 5 Well then, does God supply

you with the Spirit and work miracles among you by your doing the works of the

law, or by your believing what you heard? (NRSV)

Paul turns from the historical and the theological to the personal and

the experiential. Though theology is at

the heart of Paul’s indictment of the Galatian Christians, it is grounded in

their religious lives. This is a significant point, to my mind, that theology

grows out of the spiritual experience of the earliest Christians, in a way that

is not always valued today. The turn away from faith that Paul perceives is a

turn away from the actual reception of the good news, which Paul implies was

charismatic, though he does not explain the manner in which they “receive{d}

the Spirit” other than to combine the reception of the Spirit with the working

of “miracles among you” (Galatians 3:4). Unless, of course, Galatians 3:1 (“It

was before your eyes that Jesus Christ was publicly exhibited as crucified!”)

represents some miraculous experience of Jesus among the Galatians. Most

scholars attribute this phrase to a description of Paul’s intense preaching,

which makes sense, but could Paul not also be describing some sort of visionary

experience within the community? It cannot be proven, but the focus on miracles

and spiritual experiences within this passage challenges us to think beyond merely

effective rhetorical teaching.

I would like to reflect on this for a short time because it has often

puzzled me how Paul would come into a city in the Roman Empire, each city with

a supermarket of gods and goddesses and make any headway in evangelizing the

local inhabitants. Certainly, Paul might get a foothold in by going to

synagogues, or speaking with God fearers, Gentiles who might have had some or

significant knowledge of Judaism, the Law and the Scriptures, but this would

only be a start. In addition, it seems likely from what we know of Paul’s stay

in Corinth and elsewhere, such as Ephesus, that Paul would have set up shop and

worked in the agora, which would have

facilitated encounters with a cross-section of people, but this does not

explain why people would turn to Jesus Christ, at least not exclusively. As

significant as Paul’s rhetorical skills are, even though he denies this in 1

Corinthians 2:4, there must have been more to his presentation than convincing

speech.

Indeed, he makes a similar claim to the Corinthians as he does to the

Galatians. Immediately after the opening clause in 1 Corinthians 2:4 that “my

speech and my proclamation were not with plausible words of wisdom,” Paul

declares that he came to them “with a demonstration of the Spirit

and of power.” Since Paul speaks to a Church at odds with him in Corinth and this

is even more significantly the case here in Galatia, Paul’s reporting on

Spirit-filled and miraculous deeds must refer to previous acts of the Spirit

which those in Galatia would acknowledge and accept as truthful reporting. We

cannot identify these deeds with more precision, whether they would include speaking

in tongues, prophecy or other “Spirit-filled” activities, but these experiences

are essential for Paul’s theological argument and, again, must represent the

reality of the spiritual experiences of the Galatians when Paul first came to

them. Modern scholarship too often minimizes the claims of spiritual

wonderworking at the heart of Paul’s Gospel, which might explain both its

initial attraction and subsequent attachment to the Church, even though such

claims are difficult to define.

It is because of these experiences and the relationships Paul has with

the Galatians that he labels them “foolish Galatians,” using the word anoêtos, which could be translated as

“foolish” or “ignorant.” Paul also wonders, “Who has bewitched you?” The verb baskainô could be translated as

“bewitch” or “put under a spell,” and though Paul probably does not believe

such tactics have literally been used on the Galatians, it does indicate the

sway or power he believes the interlopers in the community have utilized in

turning them away from the Gospel he preached.

The remainder of this section reflects back on their conversion

experiences, and the religious events which accompanied them, and draws on the

theological arguments made in the second half of Galatians 2. It does so by

asking a series of questions, some of which we have already examined. The questions

are as follows:

1.

Did you receive the Spirit by doing the works of the law or by believing what

you heard? (Galatians 3:2)

2.

Are you so foolish? Having started with the Spirit, are you now ending with the

flesh? (Galatians 3:3)

3.

Did you experience so much for nothing?—if it really was for nothing.

(Galatians 3:4)

4.

Well then, does God supply you with the Spirit and work miracles among you by

your doing the works of the law, or by your believing what you heard? (Galatians

3:5)

Notice the rhetorical force of this type of questioning, which challenges

not Paul’s teaching or proclamation, but their

own experience. And yet, in both questions 1 and 4, which frame the whole

section with identical contrasts, the theological teaching of Paul distinguishing

between “works of the Law” and “believing what you heard” is central. It is

important to keep in mind here as well that “believing what you heard”

translates the noun pistis, which is

generally translated as “faith.” The phrase in both verses is ex akoês pisteôs, which is literally

“out of the hearing of faith.” “Believing what you heard” is a fine

translation, except that it obscures the commonality of pistis, which is earlier in the letter translated as “faith.”

Paul’s verbal consistency is obscured by the English translation, which is

equating “faith” with “belief.” I would simply change it to “having faith in

what you heard.”

The significance of the argument, of course, is not obscured, which is

that the experience of the Spirit came not through “works of the Law” but

through “having faith in what you heard.” In question 2, Paul equates the

“works of the Law” with “the flesh” (sarx),

since the Spirit (and justification) has come through faith. This indicates

that “the flesh” and “the Spirit” are naturally opposed.[1]

Question 3 is a typical “parental” question: are you going to throw away

everything you have already gained? If everyone is following the works of the

Law does that mean you have to do so? How did you gain the Spirit?

This sort of parental appeal has a lot of emotional pull, as anyone with

parents knows, for it plays on past religious experiences and past

relationships. These sorts of relationships, with so much history, are not easy

to cast aside or ignore, which Paul knows, and he plays on the emotions of the

Galatians. Yet, emotion will alone not win the Galatians back to Paul, since

those who have entered the community have their own appeals and their own

relationships with the Galatians. Paul will have to return to theology if he

wants to restore the relationship among the Galatians. He will have to convince

them.

Next entry, Abraham and faith

John W. Martens

I

invite you to follow me on Twitter @Biblejunkies

I

encourage you to “Like” Biblejunkies on Facebook.

This entry is cross-posted at

America Magazine The Good Word

[1]

There will be much more on the sarx and

pneuma (Spirit) contrast in this

letter, which we will discuss later in the commentary.

0 comments:

Post a Comment