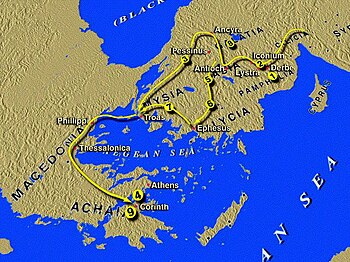

| English: Map of the Letters of Galatia (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

In

the first entry in the Bible Junkies Online Commentary on Galatians, I

discussed introductory matters concerning the founding of the churches to the

Galatians, the situation when Paul wrote to them, when the letter might have

been written and the type of letters which Paul wrote, based on the common

Greco-Roman letters of his day. In

the second post, I considered the basic content and breakdown of a Pauline

letter. I noted the major sections of the formal letter structure and, in the

context of each section, outlined the theological and ethical (as well as

other) concerns of Paul, including some Greek words which will be examined more

fully as we continue with the commentary. In

the third entry, I looked at the salutation, which is long for Paul’s

corpus (only Romans 1:1-7 is longer) and briefly commented on the lack of a

Thanksgiving, the only letter of Paul’s which does not have one. The

fourth entry discussed the opening of the body of the letter, a significant

part of the letter especially in light of the absence of a Thanksgiving. In

the fifth entry, I examined the beginning of the opening of the body of the

letter, in which Paul describes his background in Judaism and I placed this in the

context of Judaism in the Hellenistic period. In the

sixth post in the online commentary, I continued to look at Paul’s

biographical sketch of his life, this concerning his earliest life as a

Christian. In

the seventh post, I examined what Paul says about his subsequent visit to

Jerusalem to see the apostles and the Church in Jerusalem.

In the eighth entry, Paul confronts Cephas about his hypocrisy in Antioch.

The

ninth blog post started to examine the theological argument in one of

Paul’s most important and complex theological letters. In

the tenth entry, Paul makes an emotional appeal to the Galatians based on

their past religious experiences and their relationship with Paul. In

the eleventh chapter in the series, Paul began to examine Abraham in light

of his faith. The twelfth blog post, found below, continues Paul’s examination

of Abraham, but also claims that Christ “redeemed” his followers from the

“curse” of the Law.

4. Paul’s Letter to the Galatians

d) Body of the Letter (1:13-6:10):

iv) Theological Teaching (2:15-5:12): Abraham

was justified by faith (3:10-14) part 2.

10 For all who rely on the works of the law are under a curse; for it is written, "Cursed is everyone who does not observe and obey all the things written in the book of the law." 11 Now it is evident that no one is justified before God by the law; for "The one who is righteous will live by faith." 12 But the law does not rest on faith; on the contrary, "Whoever does the works of the law will live by them." 13 Christ redeemed us from the curse of the law by becoming a curse for us—for it is written, "Cursed is everyone who hangs on a tree"— 14 in order that in Christ Jesus the blessing of Abraham might come to the Gentiles, so that we might receive the promise of the Spirit through faith. (NRSV)

Before examining the specifics of this passage, it is

important to note that in this section Paul cites, reflects on and interprets

four (or five) Old Testament passages, Deuteronomy 27:26, Habakkuk 2:4,

Leviticus 18:5, Deuteronomy 21:23, and perhaps Deuteronomy 28:58. We will speak

of each of these verses below, but it is Paul’s interpretation of these verses

which leads some scholars to call this passage, including what came before and

what will come after, a “midrash.” This leads to a good question: what is “midrash”?

It is difficult to define midrash, but rabbinic and biblical

scholars seem to know it when they see it. In fairness, rabbinic scholars know

it when they see it and biblical scholars tend to see it everywhere. I will

depend upon Strack and Billerbeck’s discussion in Introduction to the Talmud and Midrash, especially drawing on pages

254-268, to give a sense of midrash. In addition, I will note James L. Kugel’s work

from Early Biblical Interpretation.[1]

“Midrash derives from the verb darash ‘to

seek, ask’. Already in Scripture the verb is used with primarily theological

connotations, with God or the Torah, etc. as object” (255). In Qumran, Strack and Billerbeck note, the

word darash is often used in the

sense of “search out, interpret” the law and the commandments (256). In the rabbinic literature, midrash indicates

“research, study,” specifically, again, with respect to the Scriptures or other

authoritative texts (256). So, it seems that midrash is the practice of

interpretation or study, although it “does not as such imply a particular

method of biblical interpretation,” and it comes as well to refer to “the

result of interpretation or writings containing biblical interpretation” (256).

Kugel notes that it includes both halakhah

(legal interpretation) and haggadah (narrative

interpretation) (68-70).

This is why it is so difficult to define. Since anyone who

comments on Scripture is in some manner interpreting the text, is any biblical interpretation

midrashic interpretation? Midrash might be considered as a sort of religious

interpretation which plays on themes and verses which share these themes to

draw out some new, or hidden, meaning in texts which make sense particularly

for the interpreter’s own context or religious needs. As Strack and Billerbeck

stress, “Midrash is not “objective” professional exegesis – even if at times it

acquires such methods, knows the philological problems as well as the principle

of interpretation in context (i.e. the explanation of Scripture from

Scripture), and also manifests text critical interests” (259). As such, modern

readers today might find that ancient writers, such as the rabbis or Paul, pull

passages from their context, whether that of a biblical book, or from historical

context, in a way that would not be acceptable today.

Underlying such practice however is a sense of the

connectedness of all Scripture, since it is written by God, and, before the

rise of historical consciousness, a means to connect seemingly disparate

passages together in order to solve textual issues for the ongoing life of the

Jewish people. “Midrash arises out of Israel’s consciousness of an inalienable

solidarity with its Bible; midrash therefore is always realization, and must discover ever afresh the present significance

of the text or of biblical history” (259). What Paul is doing in Galatians 3, therefore,

I would argue is a common Jewish practice of midrash, making sense of the

biblical passages in light of present conditions, which include for Paul the

person of Jesus Christ.

Naturally, Jews in Paul’s day, as of course today, would

vociferously disagree with much of what Paul says about the Law in Galatians, but

they would have recognized what he was doing in his interpretation. Kugel notes

that commonalities found in interpretation of certain biblical passages, such

as a verse from Genesis, located in Jubiliees,

the Old Greek of the Pentateuch, Philo of Alexandria and the New Testament

might not be dependent upon direct borrowing but on “a common store of midrash

that circulated in Jewish communities” in Palestine and beyond (71). This is

the interpretive context into which Paul’s reflection on Abraham, Jesus, the

law and faith places us.

Paul says that “all

who rely on the works of the law are under a curse; for it is written, ‘Cursed

is everyone who does not observe and obey all the things written in the book of

the law’” (Galatians 3:10). Note that this verse parallels Galatians 3:7 in

which the “sons” of Abraham are those who are hoi ek pisteôs, “those out of faith,” or “those who believe.” The

Greek in 3:10 speaks of those who are ex

ergôn nomou, “those out of the works of the Law.” The verb “rely” is not

present in the Greek. Those who believe, or have faith, are children of

Abraham, while those who “are out of the works of the Law” are under a curse.

Paul has drawn this conclusion from his use of Deuteronomy 27:26, which he

cites and which indicates that the “curse” is that one must “observe and obey all

the things written in the book of the law.” I want to note here, though, that

the key verb, in infinitive form, is poieô,

“to do” and which is translated with emmenô,

“to remain faithful, obey,” as “observe and obey.” Awkward though it may be, it

is important to note that a literal translation would focus on “remaining

faithful in order to do” all the

things of the Law. I will bring up the verb “to do” again and explain why I

think it is significant for Paul. Here, I just want to note the first point

Paul makes:

- 3:10: Paul understands the curse of Deuteronomy 27:26 as the demand to do every word of the Law.

In the following

verse Paul states that “now it is evident that no one is justified before God

by the law; for ‘The one who is righteous will live by faith’” (Galatians 3:11).

The central verse here is Habakkuk 2:4, which stresses that righteous people (ho dikaios) live by faith (ek pisteôs),

as Paul has stated earlier in the letter, and that the Law does not “justify”

or “make righteous” (dikaioutai). Paul’s point is straightforward here:

2.

2. 3:11: The righteous live by faith not

the Law.

Verse 12 in some

ways repeats the point of the previous verse, drawing on Leviticus 18:5, to

show that “the law does not rest on faith; on the contrary, ‘whoever does the

works of the law will live by them.’” Paul’s point is to stress that the Law must be done, note again the Greek verb poieô, which he contrasts with faith, as

exclusive modes of righteousness. It should also be noted that the point of

Leviticus 18:5 in its context is that doing the Law brings life: “You shall keep

my statutes and my ordinances; by doing so one shall live: I am the Lord.” Paul’s

point is different than that of Leviticus:

3.

3. 3:12: The

Law rests on doing the things of the

Law, which is not faith (the righteous live by faith).

Paul then says that “Christ

redeemed us from the curse of the law by becoming a curse for us—for it is

written, ‘Cursed is everyone who hangs on a tree’” (Galatians 3:13). As we saw

in 3:10, the “curse” as Paul outlined from Deuteronomy 27:26 was having to

follow every aspect of the law, but by becoming a “curse” for us, as found in

Deuteronomy 21:23, Paul is suggesting followers of Jesus are “redeemed” from

this “curse.” How this is the case is not clear, for Paul has brought together

two different “curse” verses. The passage from Deuteronomy 21:23 refers to

anyone who is executed and displayed publicly for all to see, a common enough

practice in the Roman period when crucifixion was common and public, but known

before this historical period also. The body of the condemned criminal is

cursed and could defile the land. By becoming this specific “curse” somehow

Jesus has “redeemed” his followers from the general “curse” of the Law. To “redeem”

(exagorazô) here has the sense of

purchasing from enslavement, so that Christ’s act on the cross has had the

impact somehow of relieving Christians from the need, it seems, to do all the requirements

of the Law, namely, Christ has “freed” them from this demand. The connection of

the Law, even in this sense, with slavery is something that would be rare in any

other Jewish midrash, but it seems difficult to avoid this implication in Paul.

There are two points, I think, which arise from 3:13:

4. 3:13: Christ redeemed us from the curse (which

is obeying every word of the Law)

5 5. 3:13: How? By becoming a curse for us, which

changes the meaning of curse, for the curse Jesus became is related to “one who

hangs from a tree.”

Why did all of this

take place? Paul wraps this up directly: “in order that in Christ Jesus the

blessing of Abraham might come to the Gentiles, so that we might receive the

promise of the Spirit through faith” (Galatians 3:14). This

does take us back to the previous installment, in which we saw in Galatians

3:8-9 that Paul understood that the promise to Abraham that all the Gentiles

would be blessed in him was fulfilled with the coming of faith in Christ. The “curse”

of the Law, in Paul’s understanding, is that every element of the law must be

done by those who follow it, but since Christ “redeemed” everyone from this “curse,”

it is faith that brings the blessing and the promise to the Gentiles. This

leads to the final point:

3 6. 3:14: Since people have been “redeemed” from the

“curse” (which is obeying every word of the Law) by Christ it is now possible

for the Gentiles (and Jews) to receive the blessings of Abraham through faith

in Christ.

Here is a question to consider: does Paul believe that

Christians are freed from the Law or from the curse of the Law? While it might

seem to be an insignificant question - do not both forms of “freedom” lead to

the insignificance of the Law? - I think it is important. One answer suggests

the Law has no remaining purpose, while the other indicates that the Law

remains active in some way or form. This is where the use of poieô (“do”) twice in this passage is

important, and will become even more important as we continue

to read Galatians. Stephen Westerholm published an article “On Fulfilling the

Whole Law (Gal. 5.14)” which claimed that Paul consistently uses the word poieô (“do”) of those who must follow

every dictate of the Law, but always uses the word plêroô (“fulfill”) to describe what Christians are said to

accomplish through Christ with respect to the Law.[2]

What “fulfill” the Law means is not easy to determine, but it is certainly not

nothing. We will spend more time on this question when we come to Galatians

5:14.

Next entry, the Promise to Abraham.

John W. Martens

I invite you to follow

me on Twitter @Biblejunkies

I encourage you to

“Like” Biblejunkies on Facebook.

This entry is cross-posted at America Magazine The Good Word

[1]

The book is co-written with Rowan A. Greer, but Kugel writes the section

dealing with Jewish interpretation.

[2] In

Svensk Exegetisk Arsbok 51 52 (1986-87) 229-237.

0 comments:

Post a Comment